Chapter 4: Society and Human Behavior

Section 1: The Anatomy of a Society

Introduction What is a Society?

This is a sociology course. Sociology is, basically, the study of society. So far, we’ve covered the major perspectives for analyzing society. We started with the three core perspectives, Functionalism, Conflict, and Interactionism including Symbolic Interactionism and other Interactionist Theories. Then we moved on to what I call the critical perspectives, Feminism and Postmodernism. We then went over some research methods for collecting and interpreting data about society. These were quantitative and qualitative research methods. We also discussed the ethics associated with doing sociological research. We are all the way to Chapter 4 and we’ve neglected the most important thing!

What exactly is a society?

Wait! What? A society is a society. Everyone knows what a society is. It’s common sense!

That’s true. It is common sense. But what did I tell you about common-sense notions back in Lecture 1? The whole point of sociology is to challenge common sense notions. To properly exercise one’s sociological imagination we really can’t take anything for granted.

So we’re not going to.

Society is a tough thing to define. Even sociologists are Inconsistent on the definition. For instance, many Introduction to Sociology textbooks don’t even bother to define society. Max Weber, the Grand-master himself, wrote a two-volume tome called Economy and Society1 summarizing his substantial social theories. He never defined society. Society is right there in the title! Weber famously defined everything. The volume begins with sociological definitions in which he even defines the word “meaning”…but no specific definition of society.

Other texts are inconsistent. My very first college sociology text, Macionis Sociology (1987),2 goes way back when I was nineteen. No, it’s not written on clay tablets! Macionis defines society as, “people who interact with one another within a limited territory and who share a culture.” Of course, that was before the internet.

Kornblum3 states that a society is “a population that is organized in a cooperative manner to carry out the major functions of life.” What is meant by cooperation? Are you in school because you are being cooperative, or are your parents making you go? Is obedience cooperation?

Newman,4 on the other hand, defines society as “a population living in the same geographic area that shares a culture and a common identity, and whose members are subject to the same political authority.” Hmm. This is a pretty common definition, but it’s problematic when you consider, say, American society. This is a huge geography full of many different cultures.

Giddens5 defines society as “a group of people who live in a particular territory, are subject to a common system of political authority, and are aware of having a distinct identity from other groups.” Ah, Newman and Giddens elaborate on an element that I think is important–identity.

All these noted sociologists have a somewhat different approach to understanding what a society is. I have my own which is a bit different still. But we should be able to agree on a general definition of what a society is. Society is one of those things that we take for granted. We are born in one. We live in one. We spend our entire lives in one. The concept of society does not really enter our minds…until it has to.

When you travel to another country, you become acutely aware of what a society is. This happens because now you must pay attention. When my family and I traveled to China, we had to figure out how to communicate and conduct ourselves.

Major disruptions that happen also bring your society into fine relief. Hurricane Katrina and, more recently, Maria were important because they tested our sense of responsibility toward each other. These natural disasters wreaked disproportionate destruction on the lives of the poor, while the wealthy fared significantly better. These events forced us to confront the uncomfortable reality that some members of our society are largely excluded from its benefits.

Our nation’s response to The Great Recession raised questions and challenged the legitimacy of our political-economy. Many social observers, especially sociologists, noted that while large, wealthy financial institutions were “bailed out,” millions of working people lost their homes, or were “sold out.” The concentration of wealth and the deference that the wealthy received from our elected officials at the expense of everyone else was exposed.

When the United States invaded Iraq we received a tragic lesson in what happens when the power structure in a society is removed. Instead of the relief and sense of liberation that our leadership expected, Iraq descended into a brutal civil war between competing cultural, religious, and political interests.

Each example above forces us to confront questions about our mutual responsibility toward each other in a given society. They also reveal the cracks and fractures of society and test the limits of relations that hold a society together. A better understanding of these things will help us make better social decisions. This is especially important in our current “polarized”6 atmosphere, where our political institutions seem hopelessly, and even aggressively divided.

So okay, Mr. Andoscia. Get off your soapbox, stop preaching and tell us what society is.

Imagined Communities

All right. Calm down. It’s not that easy. When we are dealing with a commonsense notion it’s best to just start from scratch. For this reason, I like to reference my friend, the Confused Martian. My Martian friend has no preconceived notions about the human world. It’s my job to explain even the most basic concepts to him. He’s very logical, rational, and inquisitive. He’s really a little annoying, come to mention it. So how can we describe a society to a Martian who has no idea what a society is?

First, we must start by figuring out what all the other definitions have in common.

For instance, of the definitions I’ve shared, and others that I’ve read, there are recurring themes.

- All of these definitions reference geographical location.

- Many sociologists also mention culture when discussing society

- In many cases, some form of government or authority is important.

- Many sociologists also recognize that society overlaps with identity.

All of this makes sense. When we imagine something like “American Society” we often see a map of the United States.

We can also imagine what we mean by American “culture.” When we think about American culture some symbolic representations come to mind. The flag. Blue Jeans. Rock n’ Roll Music. Apple Pie. Hamburgers. Baseball. Uncle Sam, the Fourth of July. The Superbowl.

We also imagine a government, represented for better or worse by the President, an authority to whom people who consider themselves American are answerable.

Furthermore, being an American becomes a part of our identities. We imagine that who we are is related to the geography, culture, and legal authority where we live. When my family and I were in China, this became an obvious reference point. We were Americans. That fact entered into the Chinese imaginations of who we were and how people were inclined to interact with us.7

It’s fair to say that societies are constructed with all four of these elements. Yet, it’s still confusing to Mr. Martian. If you were paying attention to my descriptions, you may have noticed the recurrence of a certain term. Imagine. We define society based on what we imagine to be true for members of such a society, including ourselves.

That’s why Benedict Anderson, in his study on nationalism, declares that societies are Imagined Communities.8 When we talk about American society, or any other society, we are likely imagining the same thing. We understand that there is a difference between living north of the 49th parallel and living south of the 49th parallel. There’s no real physical boundary there, but we know because of historical, legal and cultural precedent that the first is the society known as Canada, and the other is the society known as the United States. This is an example of everyone having a consensus about the boundaries of a society.

Negotiating Consensus and Conflict

Where we have a consensus about society, things run pretty smoothly. It’s always in the interests of society to develop a social consensus about the rules of living in the society.

Sometimes, however, there isn’t a consensus, or the consensus breaks down. When there is no consensus, we have conflict. Take, for instance, our current debate over immigration. This is an issue that cuts across a foundational understanding of society, namely, who are members and who are not. If we define a society based on geography and political authority are we saying that everyone within those boundaries and subject to that authority are full members of society? In the United States, no, we are not. In the United States we have a tradition of birthright citizenship. This traditions was codified into law in 1868 with the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. People who were not born in the United States, and wished to become members must go through a process called “naturalization.” This is, in sociological terms, a ritual performed so as to be recognized as a member or “citizen” of the society with all of the benefits and responsibilities that the society offers. We have established norms on what constitutes a “citizen,” but we don’t all agree on the validity of those norms. Some are starting to question birthright citizenship while others believe we should offer fewer opportunities for naturalization.

There is even less consensus about those who do not fit our definition of citizen. How should American society respond to non-citizens? Should they be allowed to freely enter our society and participate as if they were full members? Should they be allowed in with limited benefits? Should only a certain amount be allowed, or should we be selective about who comes in? Should they be completely excluded? If so, how much energy should be put into keeping them out? If we are going to exclude or limit entry, what about people who sneak in? How do we deal with people who technically break the law by crossing our boundary but otherwise participate in perfectly legal and even beneficial market activities like farming, domestic work or unpleasant factory labor? What if they are in the United States for many years without incident? Can they earn some benefits or is their membership defined by one act of crossing an imaginary border? What if they have children while in the United States? Those children are, by law and tradition, members of our society, but the parents are not. What about people who sneak in with young children who live their whole lives in the United States, who identify with American culture despite not being born in the United States or going through a requisite ritual to establish membership?

No matter how you feel about these questions, and I certainly have my opinions, they are matters for which we as members of the United Statesian society do not share a consensus. This is a foundational issue of any society…who gets to be recognized as a member? Where there is conflict, we have to figure out how to create a consensus. Such conflicts are natural in any society. Societies usually find ways to resolve such conflicts that are recognized as more or less legitimate. Often, we argue about these things in the political sphere and decide on laws to guide our actions. Sometimes we argue about these things in the cultural sphere, in which case we develop traditions and norms that guide our actions. This process usually works well, but sometimes these conflicts lead to polarization, or divisions within the society for which no compromises are difficult to make. When the consensus breaks down, this can lead to animosity, violence, even civil war.

With this in mind, we can settle on a definition of society. A society, is an ongoing negotiation between recognized members on the norms and values that should guide their collective lives. This understanding of society, as a negotiation, is central to my approach to studying society. As you can imagine, the more people you have in a society, the more complicated this negotiation.

Yet, in most issues, societies do a good job in negotiating. It’s easy to look at conflicts and think that everything is coming apart at the seams, but think about it. I can go from my home in South Florida to Seattle, Washington. It’s thousands of miles across the country, but I’ll be able to get around just fine. I’ll know the rules, the language to use, the symbols to interpret. The negotiation has already taken place. I’ll be perfectly comfortable. On the other hand, if I were to travel to Cuba, only about a hundred miles away, I’ll face more difficulties. I’ll have to learn how to navigate that society. It’s one with which I’m not familiar. These boundaries may be imaginary, but they are very real in their consequences.

So how does this happen? I don’t know anybody in Seattle. How is it I can travel there and get along just about as easily as I get along in my own home town? The United States is a society of over 330 million people and, on most things that organize our lives, we agree. How does that happen?

Social Structures

That’s the beauty of societies. As they grow and develop they create social structures to meet the needs of the society. In a phrase, these social structures are socially constructed. We learned about Social Construction Theory in Chapter 2, Section 4? Social structures are defined and predictable patterns of behavior within a given social context.

I was a teacher in a school in Southwest Florida. Let’s say I were to move and teach in a school in Seattle. Despite the distance and the geographical differences, I would understand my role as a teacher and be able to predict what that interaction would be like. Schools are social structures.

Social structures consist of norms, roles, and statuses. Norms are rules for participating within a given structure. These rules may be formal, in that they are written down with clear consequences, or informal rules for group interaction. Roles are the expected behaviors and responsibilities of each member of the interaction. For instance, as a teacher, the role I play in the interaction that takes place in the social structure called a classroom is defined differently than the role defined as student. Status defines who receives deference from others and privileges that others do not have. For instance, in a classroom, my status in my role as a teacher gives me the power to give grades. Students don’t get to grade me in quite the same way.

Many of the behaviors and interactions that take place within a social structure are ritualized. In other words, they can be described in terms of ritual performances. Doing the Pledge of Allegiance every day is an obvious example of a ritual. Less obvious, but equally ritualized, are such behaviors as taking notes, raising your hand to speak, and other defined behaviors you perform at school. When you start looking at behaviors in terms of rituals, you see them everywhere. Taking a test is a ritual. Meeting a friend for lunch is a ritual. Most of our day involves no thinking at all. We just perform the established rituals.

How we communicate within social structures is often scripted. I meet you, I say hello. You say hello, how are you, I say I’m fine how are you. You say, I’m doing great and walk on. Everyone’s happy. That’s an example of a script. Much of what we say and talk about is already laid out to us in the structures that are established. When our interactions are unfamiliar, and we are not clear on the rituals or the scripts, we often feel some discomfort. Fortunately, under such circumstances, other rituals are performed, and scripts used that are intended to put a newcomer at ease. For instance, we may perform an introduction ritual, or participate in the ritual of small talk until everyone in the interaction is comfortable.

The whole point of having a structure is to create a stable set of expectations in which to act, in which individuals are not expected to innovate behaviors or renegotiate interactions. Imagine how difficult it would be if every time we entered an interaction we had to figure out the rules of that interaction and then negotiate those rules with everyone involved? Structures make it possible to conduct most interactions almost automatically.

The Sociological Perspectives and Social Structures

So where do these structures come from and what do they do?

Well, that depends on how you look at social structures. You have learned the major sociological perspectives, and each of them have somewhat different approaches to understanding social structures.

Structuralist Structures

For instance, Functionalist sociologists see social structures as providing order and stability to society. Structures are functional and serve to stabilize and organize our lives in such a way that makes social life possible. Social structures are organic to society itself. As society evolves, so do its component structures. Functionalists have a positive interpretation of social structures. They see social structures as necessary technologies for constructing a Social Consensus.

This contrasts with Conflict Theorists. For conflict theorists, social structures are imposed by dominant groups onto less powerful groups. The social structures serve to preserve dominant groups at the top of the social hierarchy.

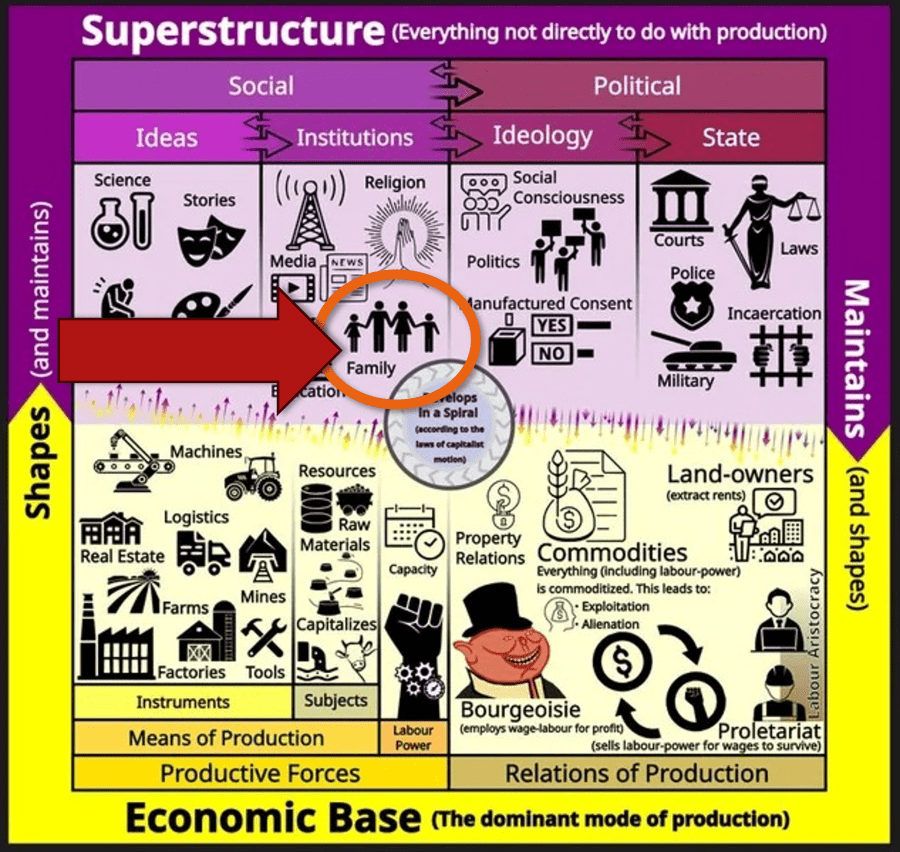

The best example of this is Karl Marx’s concept of the Superstructure.9 Marx saw society as resting on economic foundations, presided over by an economic elite. This economic elite uses its wealth to fund and finance other structures like the state, education, religion and culture. These structures, form a superstructure that supports the legitimacy of the economic elite. This superstructure teaches the proletariat, from the soapbox, the classroom, or the pulpit, that capitalism is the right and natural way to run a society. For Marx, this superstructure creates an alienating False Consciousness that keeps the proletariat from rising against its oppressors.

The functionalists and the conflict theorists are very interested in structure. They have a top down understanding of society, what we call a macro level approach. That’s why they are understood as being “structuralist” approaches to sociology.

Nonstructuralist Structures

The interactionists, however, flip the script on social structures. Instead of understanding social structures from the top down, the interactionists understand structures as the products of interaction. In fact, some symbolic interactionists even reject the validity of structures completely. For them, only interactions matter. Berger and Luckmann’s theory of the social construction of reality explains structures as habituated interactions, or interactions that have been repeated so many times that they become understood as the right and natural way of doing things.10 They become the accepted reality.

One of the most comprehensive theories from this tradition is Anthony Giddens’ Theory of Structuration.11 For Giddens, social structures are composed of rules that reproduce the structures and resources that allow those within the structures to get things done. Giddens sees social structures as having a dual nature, which he refers to as the Duality of Structure. Structures are the medium by which things get done and structures are the outcome of doing these things. For instance, your school has resources like books, computers and teachers as well as rules, like a curriculum, that are recognized as an education. Schools are the medium by which you receive an education. Schools are also the outcome as they become the recognized structure for getting an education. When people want an education, they seek out schools.

Critical Structures

The critical perspectives also have somewhat different approaches to understanding structure. The feminist perspective, for instance, sees structure in much the same way as conflict theorists, as an imposition. In this case, the structures were created by men to benefit men12 and to maintain a system ruled by men. Male dominated societies are call patriarchies, and their structures are patriarchal.

The postmodernists have a very radical approach to social structures. Postmodernists, claim that social structures can be deconstructed into metanarratives, or the agreed upon way we talk about things. When we talk about our education, our personal education narratives, it’s understood that we are referencing the process that we all went through in school. These metanarratives are not constants, they change over time. Once upon a time our education was a product of our family lives, or apprenticeships, or our personal networks. But today the narrative defines education in terms of school. It doesn’t have to. We could recognize education in terms of going to the public library and reading all of the books. In the future, education may be defined in terms of the internet and virtual reality.

The bottom line is that, for postmodernists, structures are not permanent, definable things. As societies become more technologically sophisticated, and communication networks more personalized, collective agreement on what is and is not true becomes harder to sustain. Societies become fragmented.

Furthermore, postmodernists recognize that the traditional structures, or metanarratives, are becoming less influential and definitive in our lives. Instead, we are increasingly developing our own personal narratives. If these narratives are being influenced by larger social forces, they are the media, technology and the consumer marketplace rather than the traditional sources of religion, traditional culture and the state.

Now social structures are probably the most broad category of concern for sociologists. Remember, the sociologist is interested in how these structures influence human behavior and interaction. Another way of describing social structures is as structured human behavior. Imagine a society like the United States, with over 330 million people, all doing their own thing. The society known as the United States would not be possible. Imagine driving with no rules of conduct or structures to constrain what you or anyone else does. Human behavior must be structured if it is to accomplish anything. Social structure describes how human behavior is organized within a society.

Institutions

But how are they organized? What do these structures look like.

For all practical purposes, social structures are organized first into Institutions. Institutions are the workhorses of society. Institutions are social structures dedicated to meeting the needs of society, such as securing resources, socializing the young, distributing power, etc. The major institutions in society include The Family, The State, The Market, Religion, Education, The Military, Health Care, The Media. We can also include Recreation and Leisure.

Functional Prerequisites: AGIL

Institutions are the social structures primarily responsible for satisfying what sociologist Talcott Parsons referred to as Functional Prerequisites of society.13 According to Parsons, in order for societies to thrive they must find ways to fulfill four functions represented by the acronym AGIL.

First is Adaptation: Societies must find ways to adapt to the physical environment. This is done by acquiring, developing and distributing resources. The economic system is largely responsible for this requirement.

Second is Goal Attainment: Societies must provide the resources by which individuals and groups can achieve their goals. Societies must also find ways to deal with any conflicts resulting from discrepancies between individuals and groups in pursuit of these goals. Government, or what Parsons refers to as the “polity” takes on this task.

Third is Integration: Societies must find ways incorporate new members, and get all of its members and constituent groups to work together. They must develop a sense of solidarity. Our social systems like family and education are central to this goal.

Finally, Parson’s refers to Latent Pattern Maintenance, or your textbook might define as Latency: Latency refers to the need for societies to be stable. This is done by the creation of shared values which is carried out by the cultural system. For Parsons, this meant religion, but I think we could add mass media to this analysis as well.

Organizing Human Behavior: Social Groups

Institutions are responsible for meeting the needs of society. To meet these needs, institutions must structure human behavior and interaction in such a way that guarantees this outcome. How do institutions do this? Well, there are both formal and informal ways of organizing human behavior and interaction within social groups.

Most social groups are informal. When people interact on a more or less regular basis and consciously recognize themselves or can be identified as members, they have formed a social group. A great deal of an individual’s life is taken up negotiating acceptance into and roles and statuses within social groups. We all belong to multiple social groups each with different expectations from us as individuals. So our family, our peer groups, those we work with, the band we are members of, the church we attend. All of these are social groups.

The smallest social group is what German sociologists Georg Simmel called a dyad.14 Dyads are social groups of only two people. A marriage, or the relationship between BFFs is an example of a dyad. Dyads are intrinsically meaningful, but often unstable. If one person in the dyad leaves, no more dyad.

The next step up from a dyad is, of course, a triad. This is a group of three people. Think of a band, a lead guitar, rhythm and a drummer. Triads are intrinsically more stable than dyads. Say, the drummer leaves the band, the band is still a band. They can just find another drummer. Triads are also the smallest social unit in which a coalition can form. A coalition is a subgroup composed of members who join together in opposition to another subgroup. In a triad, it’s possible for the rhythm and lead guitarist to conspire against the drummer.

Groups can also be divided into primary and secondary groups.15 Primary groups tend to be long term groups that are emotionally oriented, held together by personal bonds. Think about families or peer groups. Your crazy Uncle Henry might not be someone you would normally hang around with, but hey, Whatayagonnado, he’s family.

Secondary groups tend to be short term and are task oriented. Think about the people you work with, or volunteer groups or classrooms. These groups come together for a particular purpose, and that purpose is what binds the group. When the task is done, say you’ve finished the curriculum for a particular class, the group comes to an end.

Secondary groups are more likely to be formally organized. Groups that are structured through formal, often legal, processes for a specific purpose are called organizations. Organizations have certain characteristics. First, in organizations, there is a clear, well defined hierarchy. All groups have leaders, but in organizations there is a formal process for understanding who the leader is and well defined benefits to being the leader. In most business organizations, for instance, you’ll have a CEO and other executive officers. Below them are managers who may have supervisors working under them who are in direct oversight of workers. This is what is meant by a hierarchy. Everyone knows who is in charge and who to go to for particular needs.

Organizations also have a formal division of labor. This division of labor, for larger organizations takes the form of a bureaucracy.16 When we think about the word bureaucracy, we often think of the state, but all large organizations have a bureaucracy. They have to in order to function. The bureaucracy is a formal division of labor designed to increase the efficiency of fulfilling the function of the organizations. Each function is broken down into its elemental tasks and these tasks are relegated to individuals who become experts at that particular task.

The most immediate organization that everyone watching this video is familiar with is your school. Your school is an organization responsible for providing a formal education process. Your principal is in charge and delegates the job of running the school to vice-principals. A vice-principal is in charge of the curriculum. One is in charge of the school building. One is in charge of special education and discipline, etc. Guidance counselors help students navigate the issues that arise in their lives and planning for the future. Teachers present the curriculum according to departments, language arts, math, social studies, science, etc. Maintenance staff and janitors take care of the building. Secretaries, paraprofessionals do the office tasks. There are a lot of people involved in running a school. These people and tasks are organized into a bureaucracy. Then take a look at where you live and all of the schools in your district. My school district has over 90,000 students. That’s about the population of Dearborn, Michigan. It would be impossible to teach that many students without some serious organization going on.

Of course, the foundational element of all societies is individuals. Society can be seen as the environment in which individuals interact. As individuals, we interact within and between many social groups. Think about all of the social groups you’re a part of. You are a part of your family. Your family may be subdivided into your siblings, your nuclear family, your extended family, your cousins. Then you go to your bus-stop. If there’s more than one person there, that’s a social group. You get on the bus. That’s a social group. You may have people you sit with regularly. The back of the bus may be a separate social group from the rest of the bus. You go to your first period class. Second period. You have lunch with your friends. You participate in clubs. You are part of a sports league. You may have a job.

The fact that people move from one group to another group is an important feature of society. In doing so, human societies composed of social groups are held together by networks. Networks are relationships that we have that connect us to other people whom we do not know. These networks help us gain access to resources we otherwise would not have. Need tickets to the Yankees game on Friday, but they’re sold out. Don’t worry. I know a guy! You don’t know the guy, but through me, this guy is going to help you get to the game. You’re welcome!

It’s networks that are most influenced by modern communication technology. I look out on my school’s courtyard and what do I see? Students are grouped much the same way my classmates were grouped when I went to high school. No…it wasn’t in a cave. Students carry on conversations and joke around, just like always, but now, with cell phones, these same students are also networked beyond the courtyard. I’d like to think that there might be a social group in my South Florida school courtyard, gathered before the bell rings, and because of the cell phone, that group is networked with another similar group of students gathered in, maybe New York waiting for their bell to ring. Either way, social networking via the internet is really challenging our concepts of society and interaction.

A final feature of a society is communities. Communities are social groupings through which an individual derives a sense of identity. A community may be based on locality. People who live in, say, Queens share an identity and fellowship with others who live in Queens. That’s a community. A community may also be a reference to a larger social category, such as a profession or social movement. As a sociologist, I derive a sense of identity and recognition among other sociologists. Mets fans form a community among sports lovers.

So there it is, Mr. Martian. I’ve just given you a description of a society in a nutshell. It could be said that a society is a collection of networked social groups that share a perceived affinity and collective identity based on geography, shared culture and answerable to a common authority. But it’s hard to break the word “society” down into simple terms. After all, everything that I mentioned in this chapter will be elaborated on in more detail in later chapters.

This is what makes sociology challenging and fun. Even the most central concept of our discipline cannot be taken for granted and is subject to scrutiny.

Anyway, the next chapter will deal with socialization and how sociologists address the nature-nurture question. See you next time.

Footnotes

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. University of California Press, 1978 ↩︎

- Macionis, John J. 1987. Sociology. Prentice-Hall. ↩︎

- Kornblum, William. 2005. Sociology in a Changing World, 7th ed. Thomson Wadsworth ↩︎

- Newman, David M. 2008. Sociology: Exploring the Architecture of Everyday Life , 7th ed. Pine Forge Press. ↩︎

- Giddens, Anthony, et al. 2012. Introduction to Sociology. Norton. ↩︎

- Klein, Ezra. Why We Are Polarized. Avid Reader Press, 2020. ↩︎

- In this case, everyone we met was wonderful and gracious, though there were some tensions. My wife and daughter are redheads. In Beijing, they were constantly subject to having people pluck out little strands of their hair! ↩︎

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso Books, 2006. ↩︎

- Marx, Karl. A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Progress Publishers, 1970. ↩︎

- Berger, Peter L., and Thomas Luckmann. The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Anchor Books, 1966. ↩︎

- Giddens, Anthony. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. University of California Press, 1984. ↩︎

- More specifically, to benefit a small minority of men. ↩︎

- Parsons, Talcott. The Social System. Free Press, 1951. ↩︎

- Simmel, Georg. Sociology: Inquiries into the Construction of Social Forms. Brill, 2009. ↩︎

- Simmel, Georg. The Sociology of Georg Simmel. Edited by Kurt H. Wolff. Free Press, 1950. ↩︎

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Edited by Guenther Roth and Claus Wittich. University of California Press, 1978. ↩︎

Leave a comment